JUST DRUNK? THE HARMFUL USE OF ALCOHOL

THE GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

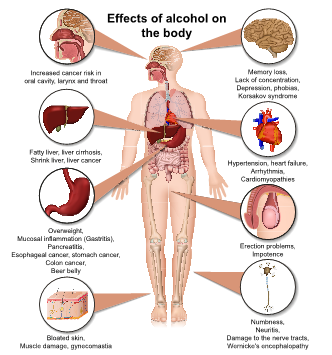

Worldwide around 3 million deaths per year result from the harmful use of alcohol (1). Excess alcohol consumption can cause a constellation of physical and mental health problems, as well as social and economic harms. The WHO has drafted a Global Strategy aimed at addressing this worrying problem (2).

Over 7% of Hospital admissions in the UK are related to alcohol (3). The overall burden from alcohol associated problems on Health care services is far greater than this; with many more patients being assessed in Accident and emergency, Primary care and in Outpatient departments.

THE VIRTUAL DOCTORS’ PERSPECTIVE

The Clinical Officers in the Facilities we support in Sub-Saharan Africa face similar challenges: they often have to deal with conditions where alcohol is a causal or contributing factor.

The Virtual Doctors have consulted on management of patients with both acute and chronic alcohol related problems. We have discussed cases of low mood and attempted suicide where alcohol has played a role. Our advice has been sought for management of patients with acute abdominal pain or vomiting following excess alcohol consumption. We have offered our opinion on cases where patients with a history of alcohol misuse have presented with features of suspected chronic heart or liver damage. We have suggested that patients are screened for alcohol excess in a wide range of clinical scenarios; from suspected nerve damage in the feet to erectile dysfunction to jaundice. We have supported our Clinical Officers when they are faced with emergencies precipitated by harmful drinking, such as gastrointestinal bleeding and alcohol related seizures.

Our Volunteers are all too familiar with these scenarios from UK based practice. We are familiar too with the difficulty of assessing intoxicated patients. These patients can sometimes be aggressive or combative. But the danger is that when an intoxicated patient becomes drowsy, that this is ascribed solely to the effects of alcohol and that another illness or condition is overlooked.

The Case: Just Drunk?

A 32-year old man was referred from Kabengeshi Health Post in Mkushi District, Central Province. He had been brought in after being found by the side of the road, unconscious. The assessing Clinician had sought further history and established that this gentleman had left home, without eating, the previous day. He had been seen drinking beer and spirits throughout the day. He had not returned home. At the time of referral, he had no temperature but was said to appear sweaty. He smelt strongly of alcohol. The main concern was that he was not responding and not talking. He had been placed in the recovery position and given intravenous fluids. The facility was not able to check the blood sugar but had sensibly given him dextrose in case hypoglycaemia was contributing to his presentation. A rapid diagnostic test for malaria was checked but this was negative, as was his HIV status. No further investigations were available on site. The Clinical Officer was worried that, despite their interventions, he remained unresponsive. They were not sure that alcohol intoxication was the sole cause for his presentation.

Through our weekly Case-Based scenarios posted on the Forum, we have been sharing learning by discussing presentations encountered by the service. One of our postings covered a scenario very similar to that described above. It was not the first time that we have been consulted about how to assess a patient when they are thought to be intoxicated. From a distance our main role is to guide the Clinical Officer through a structured review; first of all, to stabilise the patient through a generic ABC assessment and then to perform a more detailed exam looking for red flag signs that may alert them to a concurrent illness. In the Forum scenario we discuss some of the potential causes of altered conscious level; trying to give the COs a checklist to consider when assessing a patient. We explain how alcohol can increase the risks of some of these conditions (such as head injury or seizures) to emphasise that a patient can both be intoxicated and clinically unwell. We flag up hypoglycaemia (low sugar) and infection as notable causes of altered conscious level to consider in any patient, because there are interventions that they can achieve immediately on site (administration of dextrose or antibiotics respectively).

In the UK we tend to treat all alcoholic patients with intravenous thiamine prior to dextrose administration, to avert the potential risk of complications caused by the build-up of toxic metabolites in the setting of thiamine deficiency. As Volunteers, we need to appreciate that thiamine is not readily available in the clinics; the risks of not treating hypoglycaemia outweigh any theoretical risk of ensuing complications from thiamine deficiency. Often the Clinics may even be short of the relevant equipment to check a blood sugar. We explain how it is important to treat on clinical suspicion in this scenario. In our discussions on the Forum we try to give context specific advice; we hope this helps both our Clinical Officers as well as new Volunteers joining the service.

Without access to laboratory blood tests or imaging on site the main decision is whether (and when) to refer the patient to hospital.If the patient has any ‘red flag’ features on exam or if they fail to improve (despite initial measures) as expected, then referral to a higher-level facility will be indicated.The main message of this teaching scenario had been to alert them to the possibility that a patient who is referred as ‘drunk’ may in fact be very unwell and still needs to be assessed in the same methodical and thorough way as any other unconscious patient.

We hope that this Forum post had helped the Clinical Officer in their initial assessment and management steps. It sounded as though the gentleman at Kabengeshi had already had a period of observation prior to the referral and yet he was still very drowsy. The CO was right to be concerned and the Volunteer talked them through assessment steps similar to those documented in the teaching case. Advice was given to assess for signs of brain infection (or other red flag features) and to have a low threshold to treat with antibiotics to cover for meningitis. The Volunteer suggested that he should be referred to Hospital for further review because he was not recovering as would be expected from acute intoxication.

He was transferred to Hospital but sadly remains gravely unwell and has not regained consciousness two weeks later. We have not heard if the underlying cause for his illness has been determined; but clearly it is more than just acute intoxication. We hope that we have helped to afford him the best possible chance of recovery. Although alcohol may not have caused his underlying illness, it could well have led to delays in care if the Clinical Officer had not had the confidence to question his presentation and seek help. Zambia’s National Alcohol Policy aims to curb the risks of problem drinking and promote a “Safer, healthier and productive Nation free of alcohol related harm.” (4) We will do our best as a Charity to work with our Clinical Officers to achieve these aims.

REFERENCES

1. Alcohol, September 2018, WHO, last accessed 15 Feb 2021 <https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol>

2. Global Strategy to reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol, WHO, last accessed 15 Feb 2021

<https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/gsrhua/en/>

3. NHS Digital 2020, Statistics on Alcohol, Gov.UK, last accessed 15 Feb 2021

<https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/statistics-on-alcohol-england-2020>

4. Alcohol Policy and Implementation Plan, 2018, Zambian Ministry of Health, last accessed 15 Feb 2021