Differential Diagnosis

“Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability. ”

The Virtual Doctors may be contacted with a very specific question regarding a defined clinical problem; how to optimise blood pressure control in a patient with hypertension already on multiple agents, how to manage a displaced lower limb fracture, what to do with a patient who has taken an accidental drug overdose and so on. These scenarios can be rewarding to deal with and the impact on patient care is clear.

However, patients do not present with a label, but with symptoms, and often the most difficult part of the assessment is to actually work out what is causing the problem. As a result, much of the casework we do involves helping the Clinical Officers decide what the most likely diagnosis is. We suggest features that would make a particular diagnosis more or less likely and we try to offer hints and tips on how to obtain clinical clues during examination.

Many of the Clinical Officers we work with through the Virtual Doctors are very experienced and have been in practice for years. Nevertheless, they may still refer cases, just as we would seek opinions and ideas from local colleagues. Often the Health Centres are run by just one Clinical Officer and thus having the Virtual Doctors on hand to discuss cases in this way is invaluable.

The Clinical Officers spend 3 years in training. The minimum entry requirement for the Diploma in Clinical Medicine is 5 O’levels. The course has both theoretical and practical components. The students undertake clinical placements from the first term onwards. The final year includes a six-month hospital attachment. This will help to prepare them for working in the field once they qualify.

AIMS OF THE PROGRAMME

The essence of training a Clinical Officer is to develop an officer who shall have acquired competence to:

1. Demonstrate knowledge of basic sciences that support the development of competence in clinical skills, practical procedures, investigating patients, and health promotion and disease prevention.

2. Perform common nursing procedures.

3. Provide first aid for common conditions in the community.

4. Take a medical history and conduct physical examinations of patients, interpret the findings, and formulate differential diagnosis.

5. Conduct child health activities and manage the sick child competently.

6. Manage common medical, surgical, obstetrical and gynaecological conditions.

7. Manage common psychiatry conditions and conduct mental health promotion.

8. Manage and participate in community health services.

9. Manage a health service facility.

10. Provide and manage medical services in an ethical manner.

11. Participate in health related research activities and translate the findings into community health action

Taken from Curriculum document for the Diploma in Clinical Medicine, Zambian Ministry of Health

The Clinical Officer training and experience leads to a broad skill set. They may see 30-50 patients a day, or more, and in these clinic sessions they may be presented with a wide range of conditions, seeing both adults and children. Generally, there are no scheduled appointment times; instead things operate more on a first-come-first-served basis. A typical rural health centre will serve a population of about 10,000 patients and cover a radius of approximately 30km, so the clinics may be very busy, especially in the rainy season.

The Clinical Officers provide Primary Care services primarily, but as well as having to manage patients in the clinic based setting they may also be presented with emergencies that they need to stabilise before referring onwards. Dental problems, obstetric cases and trauma may also present to the Clinical Officers as a first point of care.

Waiting in line at the Under 5s clinic

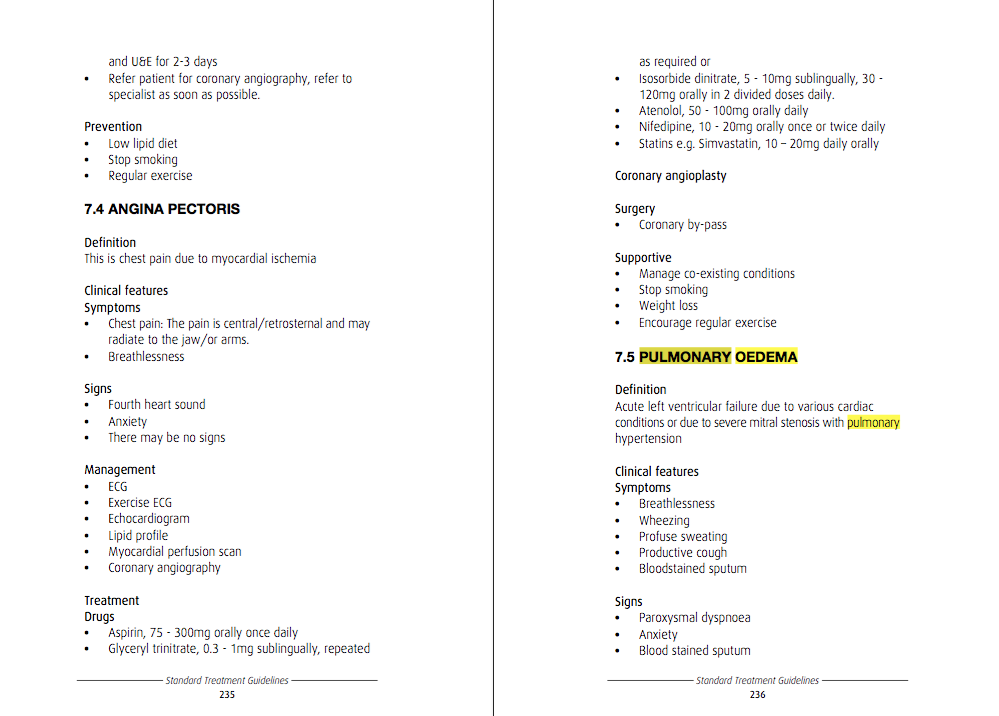

The Clinical Officers have various resources that they can use for reference, including the Zambian Ministry of Health Standard Treatment Guidelines. This publication covers many of the more common conditions that they will encounter. It is an excellent handbook, giving simple clear management advice to health care practitioners; including information about relevant prescribing and drug dosing.

Excerpt taken from the Standard Treatment Guidelines, Zambian Ministry of Health

But it is primarily a management guideline rather than a diagnostic aid; so if the Clinician is less sure of the diagnosis it is very helpful to have the Virtual Doctors to turn to as an alternative.

Kalomo Hospital CO Akende Sikota Wina giving feedback on an earlier VDrs consultation

THE CASE

A Clinical Officer contacted us to discuss a 69-year old man who had presented with swollen legs (leg oedema). He told us that the patient was normally fit and well until the symptoms started a few days ago. He attached a photo with the referral to illustrate the nature and extent of the swelling. He described the swelling as ‘pitting’, meaning that an indentation remains for a time after the skin is pressed; this is important because the causes of non-pitting versus pitting oedema are different. Similarly, it was helpful that he told us that both legs were affected because the underlying causes we think about differ if only one leg is swollen. The patient’s observations were stable. He had been started on an antibiotic and a water tablet.

On this occasion little further history was provided and the Clinical Officer did not frame a specific question. Clearly he had been considering various possible causes but there was something he was unsure about and he needed help moving forwards.

The Virtual Doctor provided a very clear discussion of the most common causes of leg swelling. They started by suggesting that in a man of 69-years old, heart failure would be an important cause of this presenting symptom. The volunteer described how asking about chest pain and breathlessness was important when considering this as a diagnosis. They went on to suggest features the Clinical Officer should look for on examination of the cardio-respiratory system to help support this diagnosis, such as clinical signs of distended neck veins or ‘crackles’ when he listened to the lungs. They then gave some recommendations about management of heart failure should this prove to be the working diagnosis. This included continuing the water tablets but also adding further medication.

Next the Virtual Doctor went on to offer alternative possibilities. Could the swelling be caused by liver failure? Excessive alcohol consumption would make this more likely and thus they suggested asking specifically about alcohol intake. They described the signs of chronic liver disease to look for on examination such as reddened palms, altered nail shape, ‘spider-shaped’ blood vessels across the chest wall and so on. Again clear advice was provided on managing the swelling in this context.

Knowing that access to tests would be limited the volunteer tried to encourage the Clinical Officer to gather as much information as possible from clinical skills alone. However, they recommended doing a urine dipstix if possible to check for urinary protein loss as this can be another cause of leg swelling. They also mentioned that dietary deficiency of protein can be a contributing factor to oedema and suggested noting the patient’s nutritional status.

The doctor highlighted that a review of a patient’s medication list is always important; side effects of drugs can often contribute to the presenting complaint. In this case they noted that the antibiotic could (rarely) cause oedema. On review of the details and the photo, the volunteer judged that there was no sign of skin infection (no redness and no signs of a fever). They recommended that the antibiotic should be stopped.

Finally, they went on to highlight that another important cause of leg swelling can be ‘dependent oedema’; it is not caused by any underlying pathology but the swelling tends to get worse as the day goes on. They stressed that it was important to ensure that the patient had been thoroughly evaluated for other causes before reaching this conclusion. They described how this condition is best managed by elevating the legs when sitting down and pointed out that if water tablets are used this should only be for short term symptomatic relief.

The Virtual Doctor had helped to create a differential diagnosis list and had given the Clinical Officer the tools to help him make judgement decisions in his ongoing management.

This is just a very simple example of a problem we might be asked to consider. Sometimes the case can be even more complex. The patient may present with a multitude of symptoms and together with the Clinical Officer we need to sort through and priotise their problems and see if we can find a unifying diagnosis. For example the patient with chronic chest pain, weight loss, cough and headaches in the setting of abnormal liver function tests. Or the patient with joint pain, vomiting, fevers and dizziness. A clinical discussion applying the ‘science of probability and art of uncertainty’ can sometimes reveal the diagnosis. In this way we hope not only to support the Clinical Officers but also to improve patient care.